In the last week I made a couple of trips from Luxembourg to Metz to hear some of the concerts at this year’s Centre Acanthes and check out the newly opened Centre Pompidou-Metz. Metz is clearly in a period of flux, rejuvenating itself with art, culture and architecture, which in all honesty outshine any of the rival major cities in the ‘Grande Région’ (a.k.a. SaarLorLux). None of Luxembourg City, Trier, Saarbrücken or Nancy quite has the quality or the creativity to match. (Though perhaps Metz comes across as particularly vibrant when full of young composers and free concerts of contemporary music.)

“Inspired by a Chinese hat found in Paris…”

When I visited last year, the Centre Pompidou-Metz was still a building site — albeit a promising one — that looked something like this:

But it is now complete and its Chinese-hat inspired roof curves elegantly over a surprisingly large amount of exhibition space.

A satellite gallery of the Centre Pompidou, though quite insistent on its own identity, it benefits enormously from its Parisian big brother’s vast collection of contemporary art. The inaugural exhibition, Chefs-d’œuvre?, ranges through Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, Man Ray, Cartier-Bresson and countless other big names, but intelligently intermingles these with related but lesser-known works and little nuggets of local art history. It carried on into more contemporary works in the three upper galleries, but unfortunately I underestimated how big the gallery is and, running out of time, could only afford a cursory glance around the first upper gallery. Seeing the unfinished spaces last year they seemed modest, but once skilfully partitioned, curated and converted into something of a maze, much more art fits in than I expected.

Luxembourg’s Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (MUDAM for short) opened in 2006, the result of a lengthy, rambling and constantly metamorphosing project. The architecture is spectacular in a sense. I. M. Pei’s design reflects the centuries of sandstone buildings in Luxembourg’s old town and even manages to give the heavy walls a weightless quality as they are slit by streams of daylight, but it is a building best enjoyed empty — a nice space to be in, but one in which the art often seems out of place. Centre Pompidou-Metz on the other hand excels in its chameleon-like ability to transform to suit the exhibition. It seems that while distinctive on the outside, its fabric is anonymous enough to recede behind the art, rather than loom over it.

Also worth visiting, is the Fonds régional d’art contemporain de Lorraine, which has had intriguing exhibitions in its small gallery spaces both times I’ve visited. Including this time this ring of indirect natural light which brought a slice of the burning European sun into this black room. It is the work of American artist Corey McCorkle and is titled Heiligenschein.

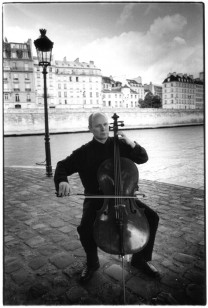

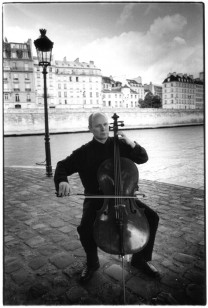

Contemporary Celli

Both my trips took in concerts of cello music. First a recital by the visiting tutor Anssi Karttunen on Friday, 9 July, and second the half a concert given by his five students on Thursday, 15 July. Karttunen is perhaps best known for his long-standing partnership with fellow Finn Kaija Saariaho, the majority of whose cello works were written for him. However, his Acanthes recital stuck entirely to Italian composers, interweaving music from either end of the repertoire’s history, from the instrument’s origins in 17th-Century Northern Italy to music of the 20th Century.

Quite possibly not to all tastes, but undeniably inventive, Karttunen’s playing has to be amongst the most colourful around. Every piece is coloured in imaginatively different ways quite unlike any other cellist I have heard, eschewing the consistent fullness of tone of the Romantic soloist for a wider palette of sound that truly exploits the instrument’s potential. This is perhaps something one might expect of a contemporary specialist (especially one familiar with Saariaho), but it is more surprising when heard in older music. It can work well though and in Giuseppe Colombi’s Chiaccona — definitely the pick of the Baroque pieces — the lightness of his colours allowed the piece to blossom quite miraculously from its ground bass into weightless, intricate, higher figuration. All the older works were played with a similar sensitivity, feeling the potential for flexibility with an improvisatory style of playing, letting tempos sway quite violently at times, but to great musical effect. Somebody described these works as ‘like sorbets’ refreshing the palette between ‘difficult’ contemporary pieces, but that seems to unfairly trivialise their role. They demonstrated how remarkably far the technique of the cello had advanced in those early years. Indeed, there is much technique in these works that is exploited in not dissimilar ways in the newer works. Obviously, the more extended techniques, found especially in Franco Donatoni’s Lame, which is filled with distant harmonics, are absent, but the dramatic potential of rapid figuration and broad spans of range are to be found across the centuries. Live recordings of two of the 20th-Century works, Donatoni’s Lame and Luigi Dallapiccola’s Ciaccona, Intermezzo e Adagio, can be found on Karttunen’s website here.

His students were in attendance to learn from Karttunen’s knowledge of contemporary music and presented a programme of Augusta Read Thomas, Carlo Forlivesi, Kaija Saariaho, Rolf Wallin, Tristan Murail and Beat Furrer (the last two both present as composition tutors). Saariaho’s Etincelles is amongst her less well-known cello works (when one thinks of Près, Petals, Amers or the more recent Notes on Light), but it could easily be played more often. Short and to the point, it makes a delightfully immediate and powerful impact with a low, violent tumult before rapidly spiralling up and away to finish. The other highlight was Beat Furrer’s Epilog, for three cellos. Quiet, trembling waves timidly broke and skated in and out of the room with a lovely delicacy that somehow managed to remain unobvious despite the repetitious nature of the material.

New String Quartets

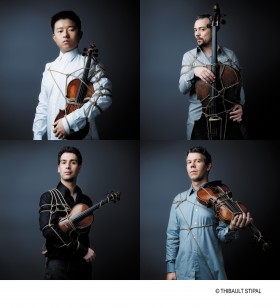

The second half of the student concert on Thursday saw the Quatuor Diotima (not quite as ludicrously attired as on their website) present three of the eleven student quartets that they had been workshopping in the course of the fortnight with a team of technicians from Ircam providing the electronic accompaniment to two of the three quartets.

The second half of the student concert on Thursday saw the Quatuor Diotima (not quite as ludicrously attired as on their website) present three of the eleven student quartets that they had been workshopping in the course of the fortnight with a team of technicians from Ircam providing the electronic accompaniment to two of the three quartets.

The second movement of 32-year-old Swiss composer Michael Pelzel’s Vers le vent… provided a vigorously energetic acoustic opener. A little like Dusapin in its tautly chromatic and dissonant harmony, but with more dramatic textural variation, an opening of quiet, rapid trilling was perforated with increasing frequency by strong accents. As often happens with such ‘unexpected’ accents that are nevertheless metered, the effect becomes unintentionally square and weakens as it goes on. Nevertheless, two excellently handled moments of withdrawal from the otherwise continuously frenetic textures revealed an assured structural mind at work and it would be unfair place a final judgement on a work without hearing its first movement.

Lisa Streich’s ASKAR, which means ‘boxes’ in her native Swedish, presented a series of more or less busy sections made up of textures of high harmonics punctuated by sharp impacts — scratches and snap pizzicati. Close microphones forced more of the bow noise to the surface, reinforcing scratchier elements as well as lending the otherwise fragile harmonics power. The proximity effect of the microphones also lent a strong bass sound to the snap pizz, which blended well with a tape part triggered by the second violinist Yun-Peng Zhao’s foot pedal. The electronic sound seemed a little muddy with the deep clangs and scrapes of the texture subject to a heavy reverb, almost evoking the quality of some early musique concrète. Over the course of the work the electronics ebbed away becoming less and less present and letting the amplified instruments reassert their primacy.

The best was saved for last with Brazilian Aurélio Edler-Copês’s masterful Quatuor n° 2: Punto rosso. The electronics, this time entirely in real time, draped each instrument’s sound in a halo of wonderful colours producing deeply rich textures simultaneously and miraculously at one with the quartet’s own colour. One might think of the electronic enhancement of the quartet sound in a work like Kaija Saariaho’s Nymphéa, but it doesn’t describe the essential quality that Edler-Copês’s processing brings to the work. So often in works of great technical skill — and this was virtuosic in those terms — one hears the misfortune of the composer’s distraction by technological difficulties and a consequent losing sight of the musicality of the work, but here was a fantastically abstract work, which relied little on clear markers or formal milestones and yet wound its way with an unobtrusive but irresistible logic. Only the final climax seemed unfortunately over emphatic or possibly under prepared, but even that resulted in a gorgeously detailed quiet coda. A related work for small mixed ensemble, Punto rosso sull’oceano, can be heard on the composer’s MySpace page, but it is no replacement.